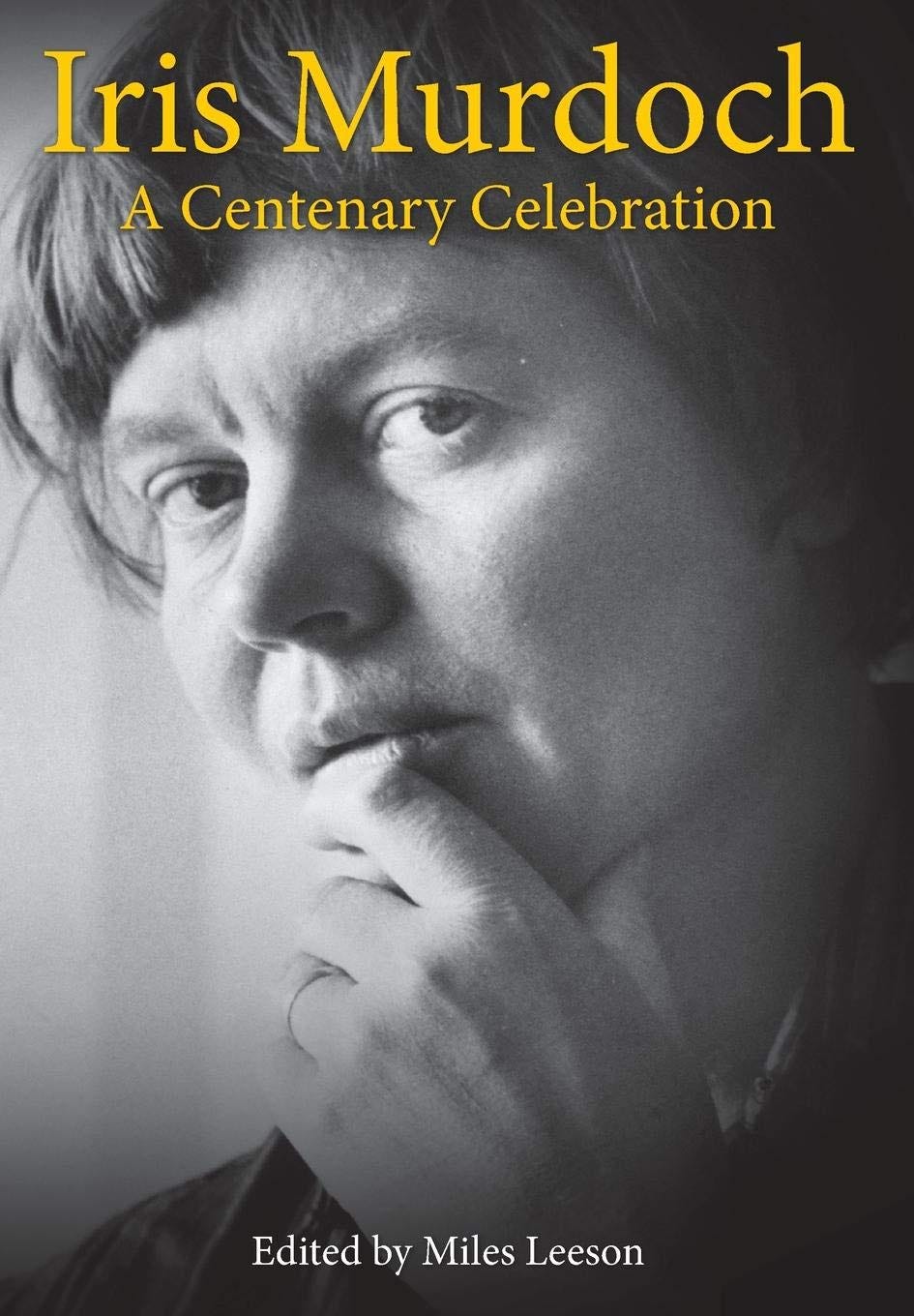

Dr. Miles Leeson: "Iris Murdoch speaks to us perhaps more urgently today than during her lifetime"

Safeguarding the great philosopher's legacy

Dear Reader,

As of late, and judging by the wider literary discourse, it seems like we are all living in an Iris Murdoch world: new publications of her books, revised translations, international conferences, articles, and comments from scholars and general readers around the globe, are (re)introducing Murdoch’s work, marveling at its richness, complexity, and relevance to our day and age. A key actor behind this movement is the Iris Murdoch Research Centre, under the steady guidance and tireless efforts of its Director, Dr. Miles Leeson.

As expected, Dr. Leeson, a reader of English Literature at the University of Chichester, England, is an authority on Iris Murdoch. But more than that, he is an utterly generous and accommodating person, eager to share his insightful opinions in order to further knowledge and research. In the interview that follows, he graciously offers a roadmap to Iris Murdoch’s novels, discusses her philosophy and its associations with other traditions, presents fresh analyses of her writings, and suggests the exploration of neglected elements of her intellectual and literary corpus. An informative and thoughtful introduction to the great philosopher, indeed.

Dr. Leeson, you are the director of the Iris Murdoch Research Centre, the hub for international research on Iris Murdoch, which publishes the Iris Murdoch Review journal, and convenes the Iris Murdoch Society. Please provide us with a brief history of the Centre and its activities since its inception as well as your own academic path and research interests that culminated in you reaching the position of its director.

Of course. The Research Centre at the University of Chichester was set up in 2016 following the dissolution of the Iris Murdoch Research Centre at Kingston University, London (I should point out though that the Iris Murdoch Archives remain at Kingston and will be there in perpetuity). Anne Rowe, arguably the leading light in Murdoch research this century, retired and, as I was focused on Murdoch’s fiction and philosophy, she asked me if I would like to take over the day-to-day running of the Society and the Lead Editorship of the Iris Murdoch Review – an offer that was impossible to turn down! Chichester University, where the IMRC is now based, was kind enough to support the transfer and we are now looking ahead to its Tenth anniversary in 2026.

My first encounter with Iris was at Masters level where I studied The Bell alongside other novels from the late Nineteenth Century through to the early Twenty-First, thinking about the novel as a form of secular scripture. Reading The Bell sparked an interest in the philosophical underpinnings of her work, which ultimately became a PhD thesis. I’ve been blessed to be able to continue this work and branch out into all areas of Murdoch’s work and her wider circle over the past twenty years. I hope this comes through on our Society podcast, which you can find here:

https://soundcloud.com/user-548804258

25 years after her death, Iris Murdoch’s books have never been irrelevant or out of date. Lately, however, there has been a significant revival of interest in her oeuvre, with many new translations of her novels all over the world, publications of books and essays, and a worldwide trend of discussing or re-discovering her work by academics and general readers alike. Why do you think this is the case? Does our current era provide the necessary ingredients and circumstances for a renewed or deeper appreciation of her writing, or is this movement a direct result of IMRC efforts?

I’m not sure how much the IMRC and IMS have contributed, but I hope a little of it is due to our outreach via the podcast and other activities. If it’s not too much of an overreach we might ask the same of Austen’s or Dicken’s novels, or even Shakespeare’s plays – why have they never been irrelevant or out of date? It’s because they deal with the human condition, the great mysteries of our lives – falling in love, mourning, remorse, powerplay, finance, exile and much else besides - as well as being (in places) very funny indeed. Whilst she might not be quite at this level, Murdoch is taking on the mantle of these canonical authors and wanting to reinvigorate that form of social realism that she considers the apex of writing. Add in her use of Shakespearean plots, and the moral vision of attention to the individual, and this forms the basis of all her 26 novels. She is deeply concerned by deracination, exile, ecology and global warming, humanities self-centeredness, the place and value of the arts in our cultural life, expressions of gender and sex outside the binary, and the place of spirituality and goodness in our secular world. In short, she speaks to us perhaps more urgently today than during her lifetime.

Remorse, spiritual crises, inadvisable sexual relationships, jealousy, power and enchantment are employed time and again, often with rather similar characters, to explore not only her own obsessions but obsessions of literature and wider culture.

- Dr. Miles Leeson

Which are the main (recurring) themes in Iris Murdoch’s fiction and which authors was she influenced by? And since she was such a prolific novelist with a career spanning decades, can we separate her works into specific “eras” each one of which with its unique characteristics?

This could be a very long answer! I’ve gestured to some of these above – Austen, Dickens, Shakespeare – but apart from these, she adores Henry James, Proust, Dostoevsky, Auden, Yeats: earlier on in her career Sartre, Beckett, Joyce. The list could go on – so some of the biggest figures in the Western Canon. I’ve also mentioned the themes that she is fascinated by, and she has a propensity to revisit them. Some critics see this as a failing but I think she returns to these because they are universals and if it was good enough for Dickens and Dostoevsky, it’s good enough for her. So remorse, spiritual crises, inadvisable sexual relationships, jealousy, power and enchantment are employed time and again, often with rather similar characters, to explore not only her own obsessions (and we see this in her collected letters that were published in 2015) but obsessions of literature and wider culture.

I think we can put a divide between the first five novels – which have been described as five different debut novels – and the period that begins with An Unofficial Rose where she relaxes into what we might call a typical Murdochian plot. Equally, we could claim a break between The Time of the Angels, her tenth novel, and The Nice and the Good; the two years between these novels is when she re-read the entirety of Shakespeare, and you can see this in her middle-period novels which range from this novel through to The Sea, The Sea. The latter novels are perhaps more concerned with magic, Eastern Mysticism, and mythology but still with all of her key concerns present. In short, we can divide her novels up artificially, but the 26 serve as a clear developmental process so it’s worth reading them in order of publication.

[Iris Murdoch] would often get annoyed at being labeled a philosophical novelist as she wished to keep these two subjects apart, but if you read the novels I think you can see that she didn’t always manage to do this.

- Dr. Miles Leeson

Murdoch’s novels are called “philosophical” which, in a way, is self-evident, given the fact she was a renowned philosopher. You have also authored Iris Murdoch: Philosophical Novelist (Continuum, 2010). As per your research, how would you encapsulate the interaction between her philosophy and her fiction?

The bottom line is they both emanate from the same mind; her writing schedule each day would include both, with the philosophy written in the early morning, then the fiction, and later in the day she would spend a number of hours responding to all the correspondence she received. In a letter of 1947 to Raymond Queneau – more on their relationship below – she said ‘Can I really exploit the advantages (instead of hitherto suffering the disadvantages) of having a mind on the borders of philosophy, literature, and politics.’ And to those subjects, one should also add theology as well. So this potent mixture finds its way into all of her novels. No, her novels are not philosophical novels like Sartre’s are, they aren’t reducible to a singular quasi-didactic vision. But her novels are spaces for play and mystery; characters do have long discussions about philosophical topics and her works are underpinned by a sense of virtue, goodness, and the need to pay close attention to the needs of the other. She would often get annoyed at being labeled a philosophical novelist as she wished to keep these two subjects apart, but if you read the novels I think you can see that she didn’t always manage to do this.

Iris’ books and her whole body of work appeal tremendously to the international audience; after all, the scenes are mostly set in London, a cosmopolitan city with constant references to other, Eastern, civilizations and cultures. Without taking a huge intellectual leap, can we suggest that Iris Murdoch’s philosophy, and by extension, literary work, is in any way connected to the cosmopolitan tradition?

Yes, I think we can. As you may know, Iris moved to London during the Blitz with her close friend and fellow-philosopher Phillipa Foot and she returned later on in her life to teach at the Royal College of Art in the early 1960s. From then on, she always kept a flat in London and was a social figure involving herself with a particular cultural circle – she stayed there three or four nights a week, returning to Oxford for the other half of the week. Anyone who wants to see the range of writers and philosophers she brings into conversation just needs to look at the Index of Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals; she was a voracious reader of philosophy both within and beyond the Western tradition, especially from the mid-1970s onwards, to say nothing of Japanese literature and history. She was intensely interested in people from all walks of life, often taking notes in pubs and on trains, and this feeds through into the novels.

At the beginning of an Iris Murdoch novel, one is often given the initial, gothic-like impression that the protagonists are in a “dark” place, entangled in perplexing situations or knee-deep in their passions and obsessions. At the end of the story, though, there is almost a “sigh” of catharsis, a sense of dispensing with the old self and entering a new state of “clairvoyance” and freedom from spiritual baggage. This purification is also the way the ancient Greek tragedies work. To what extent was Iris Murdoch influenced by the ancient Greeks and their sense of tragedy?

This is a neglected area of discussion, so I’m glad you’ve asked about it. The answer is that Greek tragedies and Ancient Greek were as important to her, especially early on in her life, as the work of Plato. She learned Latin at school, of course, and would have read Homer early on; she even considered being a scholar of Ancient History at one point. Once she gets to Oxford, studying ‘Mods and Greats’, she continues her study of Greek philosophy, Literature and Language. One of her most important classes was studying the Agamemnon with the Classics Scholar Eduard Frankel, spending months going through line by line and translating it, discussing it and reflecting. This was undertaken in a European seminar style, rather than the classic Oxford tutorial, an innovation at the time and this working through with the great master would influence the development of the enchanter figures in her own fiction. This sense of the tragic never leaves her and, combined with her love of Shakespeare, will influence so many of her key fictional scenes later on. I hope someone will write the definitive study of Murdoch’s engagement with Greek thought at some point…

It is the women who survive their encounters with them who will go on to have fulfilling and, we hope, happier lives. This is [Iris Murdoch’s] subtle feminism coming through, I think, and one that needs more examination.

- Dr. Miles Leeson

Especially as a younger reader, I was impressed by the fact that, in many of her novels, Murdoch uses male characters as protagonists who, as a consequence, narrate their life and love stories from the male gaze. Why do you think she took such a decision and what was its significance and effect in terms of popularity or otherwise?

She said that she identified more with men than with women, that she was more interested in the world of men as the world was, at this time, a world designed for men. And as we know she had relationships with men and with women, throughout her life.

What she so cleverly does in her fiction is puncture the pomposity of these self-absorbed, obsessive figures. She has been criticized for writing from the first-person perspective of men in six novels without ever giving the same opportunity to women. I would suggest that none of these men: Hilary Burde, Charles Arrowby, Bradley Pearson and so on are ever shown to be reflective or grow spiritually (well, perhaps Jake Donaghue does in Under the Net, but I think he’s the exception that proves the rule!). It is the women who survive their encounters with them who will go on to have fulfilling and, we hope, happier lives. This is her subtle feminism coming through, I think, and one that needs more examination.

In terms of popularity, these six novels – Under the Net, The Sea, The Sea, The Black Prince, A Word Child, The Italian Girl, A Severed Head – are some of her most well-regarded and most popular novels. I certainly think The Black Prince is the greatest novel she ever wrote.

In “Under the Net” (1954), we follow the escapades of the hero, Jake Donaghue, who earns his living as a literary translator. It is through him that Murdoch gives a very poignant description of the art: “I just enjoy translating, it's like opening one's mouth and hearing someone else's voice emerge.” To your knowledge, did Iris Murdoch herself engage in translating other writers? Which ones and why?

She did, but only once. She translated her friend Raymond Queneau’s Pierrot Mon Ami and was devastated when the publisher turned it down and went with another translation. It didn’t help that she was desperately in love with Raymond (and with Paris in general) but he turned her down as he was already married with children at this point. She dedicated Under the Net to him, and if you read Pierrot Mon Ami you can see the strong influence he had on her first work. Of course, she was always delighted to see her works being translated into other languages, but she did worry that her translators would pick up on all the nuances she used.

Apart from essays and novels, Iris Murdoch also wrote poetry and drama. Which of her works in these genres would you recommend? Are there other lesser-known scholarly activities of hers you have come across in your research that you think our readers might find interesting?

At present her poetry is almost entirely out of print, sadly, but there will be a new collection coming out soon! On her death Iris left around a thousand unpublished poems which we have been working through and selecting for publication. During her lifetime she only published a very small amount. We hope this will be out later this year, or early in 2025. Watch this space!

The plays are really undervalued. If you want to know more about them there was a special edition of the Iris Murdoch Review published in 2021 that covered all of her dramatic works. You can download it for free here:

https://irismurdochsociety.org.uk/product/iris-murdoch-review-12-2021/

The plays are available secondhand via www.bookfinder.com I would recommend starting with her adaptation (with J.B. Priestly, no less) of A Severed Head.

For those not yet acquainted with Iris Murdoch’s body of work, which title(s) would you recommend as a starting point?

I would direct your readers to this piece that I wrote a couple of years ago on the best place to start with Iris. https://fivebooks.com/best-books/iris-murdoch-miles-leeson/

I started with The Bell which is as good a novel as any, I think.

Apart from your current position as a Reader in English Literature at the University of Chichester, you deliver lectures for the general audience on Iris Murdoch and the themes encountered in her books. Are there any upcoming classes or activities you would like to announce?

I do! Starting in March I have a series of five online classes that this year are focusing on Iris Murdoch and Love. You can find the details here:

https://www.literaturecambridge.co.uk/murdoch-2024

The Research Centre also organizes regular public talks at my University, and we have a Christmas Lecture each year. To join, or for more information, visit the website:

Thank you very much, Dr. Leeson! Your answers are a treasure trove of insights and a stepping stone for further exploration and discovery of our beloved philosopher!

As always, thank you for reading,

Katerina