Fabio Stassi: "I believe that reading and literature in general, can save lives"

Interview with an astute observer of the human condition

Dear Reader,

Every once in a while, we stumble upon a book or an author that moves us in an unexpected way. During the past few months, I felt quite fortunate to have discovered Fabio Stassi, an Italian novelist and word virtuoso who, despite having won numerous awards and honors in his home country, is relatively unknown to the Anglo-speaking world, considering that only one of his books, Charlie Chaplin's Last Dance, has been translated into English (Granta Books, 2017, translated by Stephen Twilley). Greek readers, however, are lucky enough to have access to a number of Stassi’s works, mainly his bibliotherapy series which has stirred a buzz and has left the Greek reading community craving for more.

In the said series, we follow the adventures of Vince Corso, an unemployed Italian professor who, to earn his living, starts working as a bibliotherapist from his small apartment, offering his services of recommending literary works as a remedy to his clients’ problems and misfortunes. In each book, Corso, who faces his own set of difficulties (a troubled past, an absent father, financial struggles) is somehow involved in a mysterious case that he attempts to solve with the help of his literary companions. It is a delightful set of books where the lines between literature and life become indistinct: noir fiction meets philosophy meets current societal challenges. The most striking, though, characteristic of these works is the omnipresence of Rome as their main protagonist: apart from the obvious Mediterranean physical and social landscape descriptions, kaleidoscopic stories, carefully weaved into the multicultural and polyphonic mosaic of modern Rome, emanate a feeling that the city is alive and breathing, with each and every one of Vince Corso’s steps. As an extra special bonus, each book includes an appendix with a comprehensive list of the prescribed literary works and the “maladies” they attempt to heal.

Touched by his compassion for people’s problems, the witty remarks, and philosophical innuendos produced by his pen, I reached out to Fabio Stassi with a long set of questions that I struggled to narrow down to a mere 13. He was kind enough to answer promptly, with his distinctive and authentic style. This interview will hopefully serve as an introduction, not only to his body of work but also to a rare mind, a compassionate heart, and a relentlessly astute observer of the human condition.

Mr. Stassi, you are the archetypal Man of Letters: an author of numerous award-winning books, you are an editor at a well-known Italian publishing house, while also working at the Oriental Institute Library of the University of Rome. Please give us a brief glimpse of your studies and your career path.

Thank you. Actually, I am primarily a librarian and a commuting reader. I read and write on the train during my trips to work. It has always been like this. The train has been my university, my home, my desk. My apprenticeship in literature was oral at first: I was very fortunate to grow up in a family where many stories were told, all of which were picaresque stories of survival, migration, and adventure. I think it was there, through the voice of my grandmother and mother, that I developed the curiosity and enthusiasm I feel for people’s stories, for history and literature, which were the two subjects I ended up studying.

So far, only one of your books has been translated into English, and that is Charlie Chaplin's Last Dance. Your Greek readers, however, have an advantage as they are able to enjoy three of your books translated from Italian by Demetra Dotsi and published by Ikaros Publishing Company: “La lettrice scomparsa” [The Lost Reader], “Ogni coincidenza ha un'anima” [Every Coincidence Has a Soul] and “Uccido chi voglio” [I Kill Whomever I Want]. In this book series, we follow the crime-solving literary adventures of a "Gerard Depardieu-looking" bibliotherapist by the name of Vince Corso. How did you come up with the central idea for these books? Did you intend to write a bibliotherapy book disguised as fiction or the other way around?

It all started by chance, with my publisher's proposal to edit a book by two English authors called The Novel Cure. A very large volume was released throughout Europe, but in each country with a different curator. It is, in fact, a real, playful, therapeutic handbook. My intervention was to write a hundred pages of prescriptions that drew on Italian literature. In short, I had to prescribe Italian novels and adapt them to every kind of ailment. The process was challenging but very enjoyable. It was during that period that I began taking an interest in bibliotherapy. During the presentations that followed, I met and got to know many people, therapists, doctors, pharmacists. It was an exciting journey into a world that I knew little about, different from that of writers and critics, yet very stimulating.

Then I came up with the idea of inventing a character who, to make a living, would treat people with books. Thanks to his love for literature and trust in it, he would also be able to solve small and big mysteries. In reality, he is not so much interested in mystery, as he is in secrets which, in his view, are the reason for people’s unhappiness and their most intimate discomfort. Secrets are the areas of his interest and he likes to investigate them, but since they are secrets, he can only formulate hypotheses. And this corresponds to my idea of literature, which for me is a conjecture, a continuous inference around the truth.

As you have already mentioned, you have edited the Italian translation of bibliotherapy books by Ella Berthoud (whose guest post has appeared on COTM) and Susan Elderkin. How is the bibliotherapy landscape in Italy at the moment? Is there a rising interest in this subject as a therapeutic method for better mental health? And if so, do you feel that your books have made a contribution in this respect? How have you been inspired by the surrounding atmosphere to create your literary hero?

I happened to know and talk to many people. Yes, there is interest in the therapeutic possibilities of reading. This can be seen above all in extreme environments: e.g. in hospitals or in prisons, as it appears that in prisons that have a library, fewer inmates are fatally injured. I believe that reading and literature in general, can save lives. Especially of those who have lost faith in words. We certainly live in an aphasic time, where words are losing their meaning. I was inspired by what we experience every day, describing the quixotic revolt of a character who opposes a book and surrenders to the malaise of the world.

One of the most interesting and intriguing parts of your very contemporary Vince Corso novels is your presentation of today’s city of Rome. When contemplating this historic city, the typical foreigner thinks of antiquity, advanced culture, and empire, or even Renaissance art and architecture. But the city you describe is totally different from the romantic picture I have just mentioned: your characters live in a multiethnic, and multilinguistic Rome, a city that allows for all kinds of cultures and subcultures to exist side by side. There are, however, mentions in your books of reverse ideologies that threaten or feel threatened by this multiculturalism. So, in a way, it seems like Rome is one of the protagonists of your books; was this your intention?

Yes, Rome is one of the main characters in my books. But she is a Rome which is very far from stereotypes, and unfortunately, much closer to reality. She is an embittered and wasted city, affected by many tensions and controversies, some even racist, very common to Italian society and beyond. I described Rome as a particularly rainy city, almost South American, in some cases nocturnal and threatening, in which extreme poverty and extreme wealth coexist, but also all the languages and music of the world.

The reader is a stateless citizen, he can travel from one place to another, from one language to another, he does not need documents and permits. And the human condition applies to everyone and everywhere. Maybe writing is just trying to give a shape to something that does not have a shape - that is pain.

- Fabio Stassi

Given my increasing fascination with the healing power of books, I paid close attention to the titles your bibliotherapist recommends to his “patients.” I especially noticed that many, if not most of them, were from Latin America (besides Italy and the USA). In a global context, I found this particularly fascinating because it shows that bibliotherapists of different origins would recommend different books based on their reads which, in turn, depends so much on the literary works that have already been translated into their own language or in a language they (and their "patient") speak. With new titles published every day, should we just come to terms with the fact that every bibliotherapist can only do so much, given the plethora of books available?

Yes, Vince Corso recommends the books that he loved, and that he remembers. After all, every book is a library. It contains all the books its author has read, and all the books the reader has read as well, because it is also through the books we know that we read. Due to that, if we are dealing with inspired and honest books, we cannot go wrong. Books are not sacred. Books are a pretext to talk, to communicate. They are the tale of vulnerability. They can bring out many positive things, they can help connect people and bring them closer to empathic listening and peaceful and equal forms of sharing. Perhaps, literature and reading can teach us to communicate in the right way, without violence, without abuse, but only with respect. And that in itself is a great therapeutic exercise. Furthermore, literature is a large territory without borders: the opposite of the shape that our world has taken. The reader is a stateless citizen, he can travel from one place to another, from one language to another, he does not need documents and permits. And the human condition applies to everyone and everywhere. Maybe writing is just trying to give a shape to something that does not have a shape - that is pain.

Which, in your opinion, is the biggest contribution of literature to its readers? Is it the consolation that they are not alone in what they experience? Is it some kind of lesson learned in order to better lead their lives? Is it companionship? Or something else? And what are the (possible) limits of bibliotherapy?

I think it is a cliché to say that literature does not console us. I think that we have forgotten that books bring us solace and comfort and activate all our human feelings and needs, like empathy, connection with other people, acceptance of other perspectives and that they can even change our mindset. Literature can help us look at reality without fear. It is like a pair of glasses: sometimes, wearing them can even hurt us. But it helps us make the visible visible, that is, it shows us what was already before our eyes but we could not see. Its therapeutic possibilities are similar to those of vaccines: by reading books, we find out that someone else had suffered what we suffer, or had thought what we now think. In addition to being relieved that the world is not so daunting, they make us feel a little less alone in the world. They sometimes make us experience high happiness and give us some kind of pleasure by escaping into the world of fantasy and imagination that only reading can give us. It is a declination of freedom: a way to break free from the borders we are forced to live in. The Spaniards also say that rebellion is learned by reading.

Your book “Mastro Geppetto” (Sellerio, 2021), based on the classic Italian fantasy tale of Pinocchio, is the fourth book of yours that has just been published in Greek (Ikaros, 2023). You have called it your life's work. Please tell us why the book is so important to you and what inspired you to write it.

Thanks. I still find it difficult to talk about this book because its effect on me has been immense. It is the only novel for which I have not stopped taking notes, even after I published it. I call it an estuary novel: it contains all the themes that are close to my heart: vulnerability, disease, loss of memory, illusions, misery, class struggle, loneliness, old age, madness, circus, unjust justice, and picaresque adventure. It also deals with literary notions like the centrality of the character, the carpentry of writing, the musical score, the tradition returned with another meaning and the importance of the ending. It seems that, through this book, I came to understand something that I had not understood in my entire life, but which had always been in front of my eyes. If I was able to see it, it was only because of everything that happened in the world and in my life - the pandemic, the return of war in Europe, the loss of some loved ones. After writing this book, I know I will never be able to write in the same ink again.

In your Vince Corso books, you subtly pay homage to Carlo Emilio Gadda, another great Italian writer you obviously admire. Has he inspired your work in general and if so, in what way?

I have great admiration for Gadda. He was a language genius. But he was also one of those writers who came to understand things late, not early. He did not have the gift of prophecy, but the anger of someone who always comes to understand things later. This makes me feel humanly very close to him. He is also very close to Vince, my character.

Who is your favorite writer(s), Italian or otherwise?

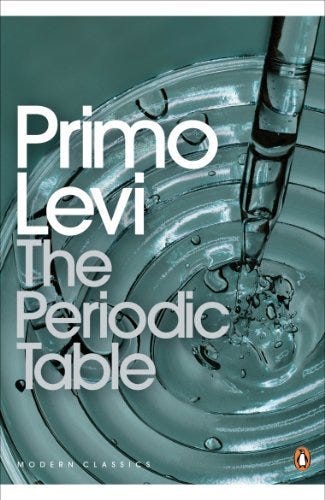

I have my constellation, like everyone else. For me, the guiding star is Leonardo Sciascia, but there are also Calvino, Saramago, Primo Levi, Tabucchi, Morante, some South Americans, and some poets.

Italy has had an enormous literary canon since ancient times. Italo Calvino has made a case for reading the classics. Has his argument been heard? Are classic works of literature widely appreciated in your country today?

Pontiggia and Calvino argued that the classic is our only contemporary. I believe that too. Unfortunately, we live in times where no space is given to the voice of the classics, and that is what generates our bewilderment.

You are a prolific writer, extensively recognized in your home country, Italy, having won numerous and prestigious awards. Do you have any professional goals you want to still achieve?

My only objective is to be honest with the reader and with myself, and to try to write as best I can. Unfortunately, one writes as one can, not as one would like. I just hope that I still have a few more ideas that make sense not only to me but to others as well.

Which books are on your nightstand at the moment?

My bedside table is a sinking boat. There is a classic, such as Manzoni's History of the Column of Infamy which I reread every two or three years, there are poetry books (I am rereading Giorgio Caproni and Charles Simic), there are travel books (currently on Albania), and a book by Thomas Bernhard.

Finally, a bibliotherapy question: we live in (seemingly) unprecedented times of huge technological advancements and societal breakthroughs. On the other hand, wars, and conflicts persist, the recent pandemic has claimed millions of lives worldwide and global economic inequalities are yet to be eliminated. Against this backdrop, which book(s) would you "prescribe" for some kind of comfort and hope to someone who is skeptical and wary of our current moment?

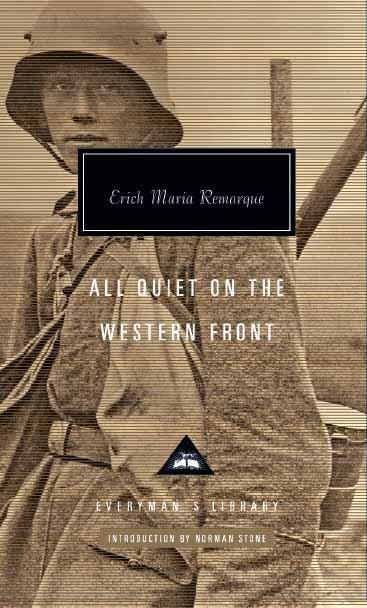

I would prescribe Ovid's Metamorphoses, ‘the greatest book’ as Calvino said, that has been written on how to maintain the continuity of forms in their incessant transformation. And then, the most famous anti-war book of the twentieth century, All Quiet on the Western Front. And finally, Primo Levi, The Periodic Table.

Thank you, Mr. Stassi, for your patience and for taking the time to answer our questions sincerely and insightfully.

If you feel inspired by Mr. Fabio Stassi’s interview, you can read Charlie Chaplin’s Last Dance or a snippet of his work in English.

You can also enjoy some photos from the recent Mastro Geppetto’s theater adaptation in Sicily, courtesy of Mr. Stassi:

Thank you for reading,

Katerina

Wonderful interview! Bravo Katerina!! "Every Coincidence Has a Soul" will definitely be my next book! I am really impressed by the idea of bibliotherapy. I need that kind of therapy. Everyone does...

All of Fabio Stassi's writings, my dear Katerina, deserve a place on our bookshelves! Hopefully, the English-speaking readers will soon get to know him better!