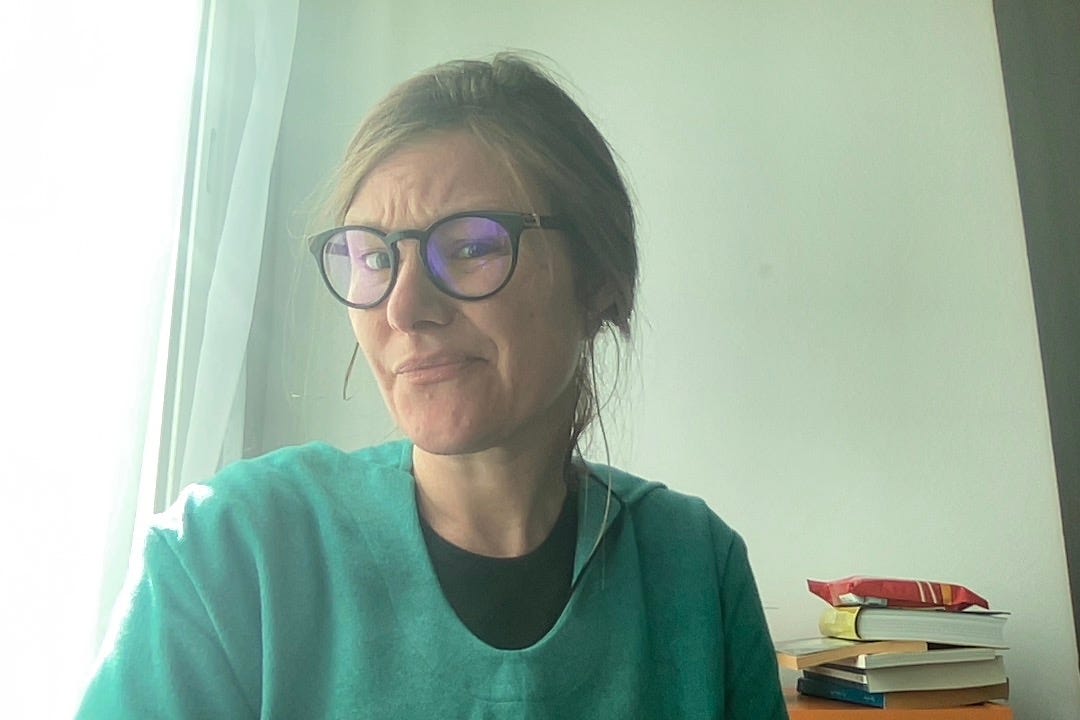

M. Lynx Qualey recommends Arabic Literature (in English)

Interview with the trailblazing Arabic literature ambassador on developing ArabLit.org

Dear Reader,

It has been 20 years since my serendipitous encounter with Arabic. In the intervening decades, my relationship with the language has been a rollercoaster -it has struggled, evolved, matured, and eventually transformed into an inextricable element of my life and identity. If knowledge, in general, has the power to change us from within, then this holds even truer for foreign languages: apart from the obvious materialistic and competitive professional advantages, they also provide an inherent understanding of diverse cultures and civilizations, ultimately diminishing our fears or at least enabling us to form data-driven opinions about “the Other.”

Back in the day, expressing a desire to learn Arabic was typically met with apprehension and skepticism, to say the least, and very few were willing to make an effort, not to mention the scarcity of instructors. In this prevailing atmosphere, I was more than grateful for Marcia Lynx Qualey’s “Arabic Literature (in English),” a groundbreaking blog connecting Arabic literature to its international audience. To me, her blogging from Egypt served not only as a source of information and entertainment but also as a long-awaited companion who made me feel less alone in my erudite interests.

Fast forward to 2024, the exact opposite is true: to paraphrase Aristophanes, under every stone lurks an Arabic teacher (although the truly knowledgable are still rare to find). At the same time, M. Lynx Qualey has become a household name for professionals and general readers who would like to get to know Arabic writers and/or translate them into English. Today’s rising cornucopia of literary translations from Arabic is a direct result of Qualey’s longtime achievements. As a token of appreciation, I turned to Marcia, who, working right in the milieu of intercultural exchange, is best positioned to offer us a bird’s-eye view and provide unique and valuable insights on the current status in the Arab literary scene and publishing industry. And her answers are GOLD.

Dear Marcia, you are the founder and driving force behind ArabLit.org, a pioneering, award-winning online literary magazine that was formerly known as the exclusive “Arabic Literature (in English)” blog. Nowadays, ArabLit informs a vast following of translators, editors, professionals, scholars, and common readers on everything pertaining to the Arab literary scene. Kindly provide us with an overview of your beginnings and the reasons why you initially started blogging on Arabic literature from Egypt in the first place.

It was 2009. I was living in Cairo and had a new baby. I had recently finished my Master’s and left the world of the university for the world of my apartment. So the blog gave me a way of speaking about things that weren’t nap times or feedings.

Or, the more direct story of ArabLit's launch is that, just before my son was born, I had written a 3000-word essay on Betool Khedairi's Absent, sent it to a literary journal, and waited several months for a response. After the positive response, I waited many more months for it to appear. When it did appear, I think in the Alaska Quarterly Review (?), I didn't get any reaction at all. It felt like dropping a penny into a void. Being published in a journal felt like the "right" thing to do, but what I really wanted was to have a conversation. Then I was reading Shakir Mustafa's excellent anthology of Iraqi short stories, simply titled Contemporary Iraqi Fiction, which I had picked up at a library in Cairo. I wanted to discuss the stories right away, not write an essay, submit it to a print journal, and then wait a year to see if anyone cared. So I just wrote a few simple reflections about the stories. I think Shakir was the first to find me, and he encouraged me to continue. So this is Shakir's project as much as it is mine.

The birth of today's online literary journal, ArabLit.org, is clearly the result of a genuine passion and enthusiasm for Arabic literature. What kinds of obstacles -material or otherwise- did you face in the process of building it from scratch and how did you endure or surpass them?

Ultimately, I think, the question was should I build it. That is: do I really look for proper funding, create a proper structure, that sort of thing. And I guess ultimately the answer was—no. For myself, I prefer it as an independent co-op of translators and writers that doesn’t bring me any money but also remains small and flexible and weird. My “real” jobs are in service of other publishers.

You occasionally translate Arabic literature into English. Which genres do you deal with most and from which dialect(s)?

I mostly work with literature for young readers, middle grade or YA novels, both because I love these genres and because I find that only a handful of translators are willing to seriously engage them. Mostly, I’ve worked with Shami authors: Palestinian, Jordanian, Lebanese, and Syrian.

In your experience as a translator, what are the common difficulties in transferring Arabic text into English? Do you find that certain texts would not “work” in the English language or culture?

Well, it depends on what you mean by “work”—and, in truth, it depends on how much work the reader is willing to put in. Certainly, there are cultural differences when it comes to readers’ expectations of a genre or form. This is especially the case with literature for young readers. What is the text supposed to do for the reader? What does the publisher expect? What does the parent expect? The educator? The librarian? The child themselves?

One example: We ultimately couldn’t publish Sonia Nimr’s Wondrous Journeys as a Young Adult novel, even though it was an award-winning YA novel in Arabic and had a large fan base among teens. The protagonist grows up—so English-language publishers simply would not agree that it was a novel for teens. In that sense, it didn’t “work.”

So we published it as regular literary fiction, and now you’ll find that in some of the reviews on GoodReads, people are confused, because they’ve read it and felt it was a book for teens. (In truth, like all the best literature for children, it’s a book for all ages.)

In terms of the cultural differences that arise between the original and translated texts, do you believe that footnotes are necessary to provide explanations? Do you feel like a cultural mediator?

I am generally not a fan of footnoted literature, except the sort of footnotes Deena Mohamed crafts in her self-translation of Shubeik Lubeik—when they’re a part of the art and the delight. A cultural mediator sounds as though I’m going to conduct negotiations. I see myself as a person who will occasionally rebuild a text I really enjoy in English, for the delight of it, in the hopes that other people will also be delighted.

Your collaborators are spread around the world. What has been your experience in remotely managing a multicultural editorial and administrative team?

It’s less managerial and more cooperative, but yes, it’s a challenge to work with many different time zones. It would be fun to work on a magazine where we were all together in one city, absolutely. Hassan Almohtasib and I have worked together more than five years, but we’ve only ever seen each other on Skype or Zoom. But this way, we get to have collaborators who aren’t in major world cities. As far as coordinating it all, the most important thing is to be flexible. So it’s good we don’t have to answer to any major donors, or anything like that.

You are a strong advocate for translating children's and young adult (YA) literature from Arabic. Are publishers around the globe interested in supporting your endeavors?

It’s a struggle. The roots of contemporary Arabic literature in English translation are in the university. In the twentieth century, the audience for most literary texts translated from Arabic to English was university students. (Translators in French and Italian tell me that, on the other hand, their genesis was more in solidarity movements.)

Even though this has changed, there is still a teacher-ish perception of Arabic literature in English translation—that it’s educational, difficult, and possibly “controversial.” Thus it could be ok for fully grown people, but not for kids. (I hope it’s clear I find this characterization to be total nonsense.)

Another aspect is that translators who come out of academia sometimes look down on literature for young readers, and don’t see it as a serious form. Fortunately, Sawad Hussain and Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp are two key translators and advocates who take literature for young readers seriously.

To me, the US and UK publishing spheres are baffling, difficult to penetrate, and require serious connections. With Arabic publishing, if I want to suggest a novel, I can usually WhatsApp a publisher.

- M. Lynx Qualey

In addition to publishing books and magazines on a small scale,

has recently started its own Substack aimed at publishing professionals. How would you describe the current situation in the publishing industry in Arab countries, and how easy is it to enter the market?Well, I’m sure my perspective is helplessly skewed. To me, the US and UK publishing spheres are baffling, difficult to penetrate, and require serious connections. With Arabic publishing, if I want to suggest a novel, I can usually WhatsApp a publisher.

In any event, there are often communication difficulties between different publishing cultures. Sometimes, bicultural literary agents can negotiate this gap. But there are few agents who represent Arabic novels well—Yasmina Jraissati, of course, but she has a small boutique agency with a short list of authors.

The newsletter is trying to help publishers (and agents) who don’t read Arabic get a handle on what’s happening in Arabic—and to introduce them to books they might find interesting. Also to translators, publishers, awards, and—of course—translation subsidies.

Arab literature is most often perceived as ethnography or cultural anthropology. Modern literary works, however, reveal a much-diversified landscape. Which genre might someone be surprised to find in the Arabic literary scene?

Well, since the Arabic-to-English literary relationship was first shaped inside the academy, anything that’s fun or frivolous can seem surprising. There were some odd critical takes on Ayza Atgowaz (I Want to Get Married) in Nora Eltahawy’s English translation, as though the book were meant to be some kind of serious academic look at the marital landscape in Egypt instead of, you know, amusing.

Do you have a favorite Arab author? Who would you suggest as a starting point for the uninitiated reader of Arabic literature?

This is like when someone asks you, Who’s your favorite child? They’re all my favorite! If you ask which of my kids you should become friends with first, well: Are you more likely to find common ground with my kid who’s a designer and cinephile, the one who talks endlessly about football, or my small editorial assistant?

So…do you like crime novels? Why not Said Khatibi’s End of the Sahara? Do you like romance? Why not try Reem Bassiouney’s Sufi-inflected romances, like the Fatimid Trilogy? Multilayered poetic nonfiction that excavates lesser-known women’s lives from the past? Iman Mersal’s Enayat El-Zayyat book, clearly. Do you love speculative fiction? The Comma Press Palestine + 100 and Iraq + 100 collections will introduce you to a lot of new writers.

Do you have kids? BUY THEM ALL OF SONIA NIMR’S NOVELS. Obviously.

From your vantage point, is there still an underrepresented country in translated Arabic literature, and if so, why?

Oh, absolutely. Of course, different language pairs work differently; there is an easier pathway for Algerian literature to get to French vs. to English, for instance. A lot still depends on translation pathways—where did translators go to study or live? With whom are their personal relationships? I think Sudanese and South Sudanese literatures are underrepresented, and generally African literatures in Arabic (except from Egypt). I also think Iraqi literature is markedly underrepresented, and has generally been overwhelmed on the English-language publishing landscape by US soldier lit.

How do you envision the future of Arabic literature (in English)?

I would love for someone else to take over the project. Or perhaps that we morph it into a project that supports the birth of new small magazines. Something like that.

Feeling inspired? You can visit arablit.org, join their tens of thousands of followers, listen to their BULAQ podcast, and support them by buying their publications. As M. Lynx Qualey said, there is something for every taste!

As always, thank you for being here.

Katerina