Prof. Charles King: An Award-Winning Historian Takes on the Origins of Cultural Anthropology

An ode to Franz Boas, his students, and their groundbreaking work and legacy

Dear Reader,

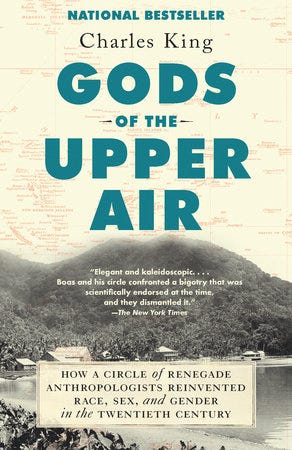

If you are a cultural anthropology enthusiast, you are probably aware of Prof. Charles King's book Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century (Doubleday, 2019). In it, Professor King does a wonderful job combining his in-depth scientific knowledge with storytelling skills to recreate the environment in which Franz Boas, a pioneer of his time and founder of the cultural anthropology field, developed his interest into a School of Thought, coined the term “cultural relativism” and engaged his students in fieldwork that would make them world famous: Zora Neale Hurston, Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, and Ella Deloria were only a few of Boas’ followers who helped establish a new way of thinking that made today's world possible.

Hailing from a deep appreciation for Professor King’s subject book as well as his general body of work, I had the immense pleasure of getting him to answer a few of my questions and I hope you will enjoy reading his elaborate and clarifying answers as much as I did.

Dear Professor King, we appreciate you taking the time to answer a few questions for our Corners of the Mind readers. To begin with, what we know about you is that you are a prominent intellectual and a Professor of International Affairs at Georgetown University. You contribute to the (inter)national dialogue through essays, commentaries, and appearances in major journals and on broadcast media. Please provide us with a brief summary of your academic and professional background to this point.

I’m very happy to talk with you—at least virtually—and to engage with your readers. I have been a professor of international affairs at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, since 1996. At Georgetown I’ve served in a variety of leadership roles as well, including as chair of the faculty of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, an interdisciplinary school of global affairs. Over the last quarter century, my interests have evolved from an initial focus on eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union—the subject of my graduate studies and several of my books--to what I suppose I would call a combination of big ideas and intimate biography. I am very interested in how world-changing ideas connect with the lives of individual thinkers and writers, which was one of the underlying themes of Gods of the Upper Air. I focused on area studies and politics in graduate school, at Oxford University, and earlier in history and philosophy as an undergraduate, at the University of Arkansas, so at this point in my career—late? middle?—I feel like I’m coming back around to themes that first energized me when I was eighteen years old (as well as the thought that I might claim the title of writer in addition to being an academic).

Apart from writing for academic purposes, you are also the author of best-selling non-fiction books for the wider audience, like Midnight at the Pera Palace: The Birth of Modern Istanbul (W. W. Norton, 2014), Odessa: Genius and Death in a City of Dreams (W. W. Norton, 2011), and Extreme Politics: Nationalism, Violence, and the End of Eastern Europe (Oxford University Press, 2010, to name but a few, for which you have been honored by numerous prestigious awards and accolades. In 2019, you published the much-acclaimed Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century (Doubleday, 2019), which was catapulted to the New York Times best-seller list and received the Parkman Prize and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. Gods of the Upper Air is also one of my personal all-time favorite books, for its enticing theme, vivid descriptions, and lucid depiction of characters. Please tell us what inspired you to write this compelling story of Franz Boas, the “father of American anthropology,” and his students.

You’re very kind to say that about Gods of the Upper Air, and I’m delighted that it spoke to you in some way. By 2015 or so, I was looking to move in a different direction with my writing. I had written several books on eastern Europe and then a book on Turkey, all of which focused on ethnicity, politics, nationalism, and large-scale transformations in human society, such as the fall of empires and the end of authoritarian regimes. As I started thinking about new projects, it struck me that my own society, the United States, was coming to look very much like places I knew in eastern Europe, with politicians dusting off old myths and repurposing them as ways of dividing society in the present—specifically the rise of Donald Trump and the radicalization of the political right in the U.S. I wanted to write something about this phenomenon and to try to find, in my own country’s history, an antidote to nationalism and xenophobia. I had also had the very good fortune of marrying an anthropologist, Maggie Paxson, some years earlier, and through her, I had learned so much about her discipline’s way of seeing the world—how it puts the reality of human difference up front as a thing to be understood and celebrated, rather than feared. In that confluence of events and outlooks lay the origin of Gods of the Upper Air. I’m always interested in finding a really great archival trove that I can exploit, too, and once I started going through Margaret Mead’s letters and papers at the Library of Congress—only a few blocks from our house in Washington, DC—I knew I had a story that had exactly the combination of things I look for in a book project: big ideas, great characters, a narrative arc, and relevance to the present.

I have always found translation such a brilliant art form, in addition to being a profession.

- Prof. Charles King

Even though culture is ingrained in the translator's methods of thinking, his/her worldview, and ultimately his/her word choice, to my knowledge, little has been written about cultural anthropology and its relationship to translation. On the other hand, language informs culture, hence language plays an important role in cultural anthropology. Based on your research and in your opinion, on what grounds can cultural anthropology be incorporated into the academic curriculum of a Translation degree and vice versa (the inclusion of translation in cultural studies and cultural anthropology programs)?

I’m not aware of research along those lines—although there may well be—but I do think that anthropologists are always engaged in their own act of translation. They are trying to write about other people, places, and societies—or “cultures,” if one wants to use that word—using a foreign language, that is, the metaphorical language of theories and concepts, as well as the literal language of the researcher. Anthropologists today are very sensitive to this fact, which is why they often engage in the co-production of knowledge with local informants, or they themselves may be “native” to the society they are studying. But that act of translating from one way of seeing the world into another is part of the anthropologist’s task—in fact, I think it’s something that any social scientist has to contend with. I can’t claim to know much about how a degree in Translation should incorporate these insights, but I do think that translators of language have an intimate sense of how difficult it is to cross the conceptual boundaries between languages. That’s why I have always found translation such a brilliant art form, in addition to being a profession—and why I always try to acknowledge my books’ translators if I happen to be giving a talk or presentation in a place where my work is known only through a language other than English.

To the uninitiated reader, which book(s) would you suggest as a primer for cultural anthropology and its place in International Relations (theory)?

There isn’t nearly enough overlap between political science and anthropology as there probably should be—which is one of the reasons that I, as someone teaching in a political science department, wanted to write Gods of the Upper Air, which is a kind of primer on a neighboring discipline written by a sympathetic outsider. Other books by Matthew Engelke (How to Think Like an Anthropologist) and Gilian Tett (Anthro-Vision) are excellent guides that also show the discipline’s unique power as an analytical tool.

Your books deal with diverse countries and regions of the world, but there is always some focus on identity, culture, and politics, namely during periods of ethnic upheavals and societal transitions. In your opinion, where does language stand vis-à-vis (the construction of) identity? Can you give us a pertinent example from your research?

Language, too, is constructed, of course, meaning that the rules of grammar and syntax that get coded as correct are always the product of some kind of state intervention: school curricula, state-sponsored language academies, and so on. But like any national form, language is good at covering its tracks—portraying a specific way of writing, speaking, or spelling as timeless and linked to an ancient identity, when in fact all of these things are intensely modern. My doctoral dissertation was about exactly this process in a far corner of Europe, in the Republic of Moldova, where the matter of what the local language was called—Romanian or Moldovan—and what alphabet it used—Latin or Cyrillic—was a matter of high politics for much of the twentieth century. Again, all of this is a very modern set of ideas, including the weird claim that humans have a natural “mother tongue” to which they should feel some sort of allegiance. In fact, the normal state of human society is for people to be multilingual, to develop pidgins and creoles when language forms come into contact, to make do with whatever they have as ways of communicating. One needs the nation—and more accurately the modern state—to convince people that they really only have one language and culture to which they owe allegiance.

I think anthropology, as it developed over the course of the twentieth century, has a set of tools and values that work directly against a limiting, nationalist, xenophobic view of the world.

- Prof. Charles King

How can cultural anthropology lead to a more open-minded attitude and “cosmopolitan” view of the world?

I am always at pains to point out that I’m not an anthropologist. I’m just an “anthropology fan,” meaning someone from an adjacent discipline who looks admiringly on what my colleagues in a neighboring intellectual realm have been up to. But I think anthropology, as it developed over the course of the twentieth century, has a set of tools and values that work directly against a limiting, nationalist, xenophobic view of the world. If your discipline begins from the fact of human difference—that different societies see the world in different ways and that your society, just because it’s yours, doesn’t have a claim to specialness—then you are very well positioned to build a science that claims all of humanity as its domain of study. No anthropologist can really go about their task properly if they start out from the view that the society they know best, their own, is somehow superior to all others. And in that orientation lies both the power of anthropology as well as its urgency in the present moment.

Because of your profession, it is anticipated that your main reads are non-fiction but do you enjoy fiction as well? Which books are on your nightstand at the moment?

I probably read more nonfiction than fiction, but I’m astonished at great novels and the sheer craft that it takes to make them. At the moment I’ve been making my way through Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead, a revelation of character and place (and in a setting, contemporary Appalachia, that makes sense to me, having grown up on a farm in the Ozark Mountains). In the last couple of years, I’ve also been reading more novels that approach the topic of the Anthropocene, such as Richard Powers’ The Overstory and now Eleanor Catton’s Birnam Wood, which is likely to be an increasingly urgent theme. And literally on the nightstand: Matthew Desmond’s Poverty by America, his follow-up to his earlier book on the housing crisis in the U.S., and Beverly Gage’s standout biography of J. Edgar Hoover, G-Man, the former FBI director and as close as the U.S. has come to a true authoritarian leader, at least until Trump.

Do you have a new book in the works?

I’ve just submitted a new manuscript to my publisher. It’s the backstory to George Frideric Handel’s Messiah—one of the greatest works of participatory, hopeful art ever created but also a product of a set of desperate lives and very troubled times, Britain in the early eighteenth century. The book has some of the things I love to write—amazing characters and large ideas, all unfolding against a backdrop of big social change—as well as a relevant message: how to think yourself toward hope when the evidence all around you points toward despair. The book, called Every Valley: The Desperate Lives and Troubled Times That Made Handel's Messiah, will be out in fall 2024.

Thank you so much, Professor King! It has been an honor!

Thanks so much for engaging with me and being interested in my work!

If you enjoyed Professor King’s interview, feel free to visit his website, buy his books, and listen to him discuss “Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex and Gender in the 20th Century” in the video below:

Thank you for being here.

With gratitude,

Katerina